|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Dear reader,

Surveillance has become an inevitable reality of modern life. We are dependent on, embedded in, and exploited by paranoid glances. With the digital sphere as our new playground, we have become voyeuristic machines, whose day-to-day lives revolve around watching and being watched.

Because of this, it can be claimed unequivocally that surveillance is not merely metaphorical or abstract, it is tangible, omnipresent, and increasingly visible. Surveillance is also a visual, image-led phenomenon. Satellites measure our existences in glitchy pixels, drones give us bird’s-eye views of our surroundings, we navigate the world through 2D grid visualisations. We have become cyberflâneurs whose habits are hardwired into tailored advertising. In the age of face-swapping and technologies that generate almost-real videos, we seem lost in a sea of information where the lifeboats are floating around us, only watching without intervening.

Although privacy remains a fundamental human right, we seem to have lost it, because it has been colonised by invasive gazes. Can this be a new Dark Age, as artist and writer James Bridle calls it? Maybe, but the first step in doing something about it is to acknowledge that surveillance has to be demystified. It is part of our daily lives; it is visible, and it seems to be here to stay.

|

| |

|

|

Petrică, Laura (Kajet, RO), Karolina, Magdalena (Pismo, PL), Pia and Stefan (n-ost, DE), Ramin — this issue’s editorial team

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

Top title image: Drone shown at the International Border Guard training organised by Hungarian police and military forces in Veszprem. Rafał Milach (Magnum) from Warsaw, for his book and series “I am warning you” on three different border walls (2019-2021).

Bottom title image: A demonstrator after being beaten during massive protests against the rigging of Belarus' August 2020 elections. There is a massive system of surveillance in Belarus, primarily carried out by the KGB RB, the Belarusian national intelligence agency. Jędrzej Nowicki from Warsaw, for his work “The Scars” (2020)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Seeing

SURVEILLANCE

Single images by photographers

from all over Europe

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Jack re-enacts a selfie he took in his Berlin flat for his social networks. Wolfram Hahn from Berlin, for his series “Into the light,” in which he explores the making of visual digital identities (2009-2010).

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Portrait created by a machine: A facial recognition system recently developed in Moscow for public security and border control surveillance. Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, for their series “Spirit is a Bone” in which they co-opted this device in order to create their own taxonomy of portraits in contemporary Russia. (2015)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Photographic staging of a surveillance system designed to detect deviant behaviour in public spaces. According to experts, there are eight different behavioural deviations: Standing still, fast movement, abandoned objects, positioning on a corner, clusters breaking apart, synchronised movements, repeatedly looking back, and deviating directions. Esther Hovers from the Hague, for her series “False Positives” (2015-2016)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

An image from Google Street View that captures a brief moment of everyday lives in Botoșani, Romania in 2012. Kadna Anda for her series “Digitally Born”, in which she tried to catch transitory moments of reality. (2019)

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The photograph of this roebuck was taken by a camera trap and put on the internet. David Zehnder from Basel, for his series “Deer Crossing” in which he raises questions about the copyright of such automatically generated pictures. (2013)

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

A Polish couple after a religious ceremony photographed with a thermal camera during the pandemic in 2020. Piotr Tracz, for his series “Life at the time of pandemic” (2020).

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

A prison cell door spyhole in a former KGB prison in Riga. Valentyn Odnoviun, for his series “Surveillance” on former political prisons in Eastern Europe (2016-2018).

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Exploring

SURVEILLANCE

A closer look at a

photographer’s series

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

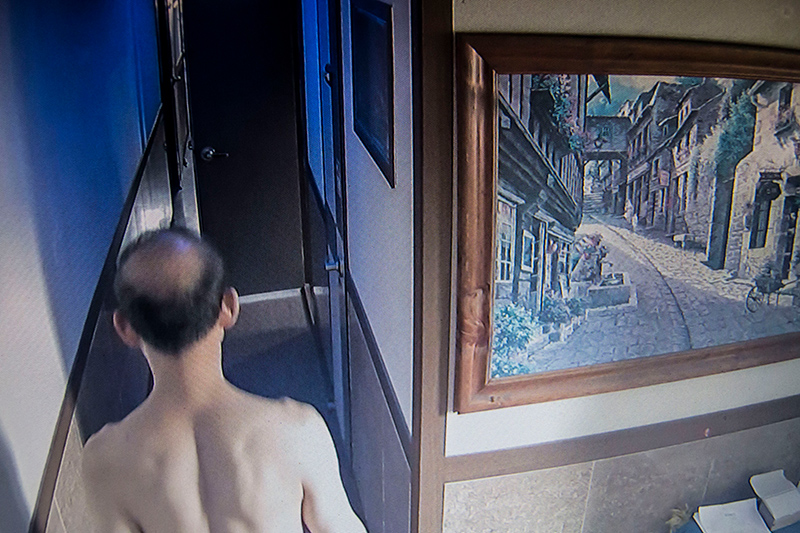

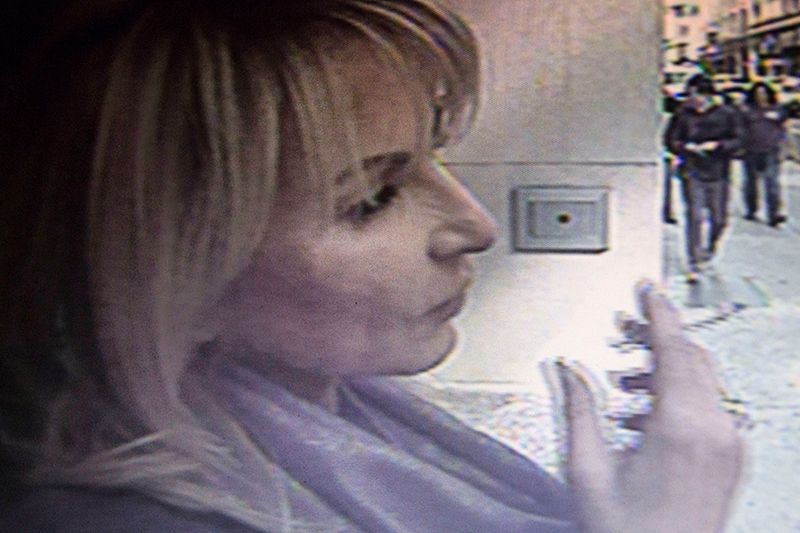

It was and is the aim of any form of power, whether it establishes itself by consensus or through fear and violence, to control people. Surveillance serves both the people and those in power. If we take a look through history, we find that surveillance has deep roots, and has always been an integral part of law enforcement. From the theocratic perceptions and the “Eye of God” symbol, which sees everything/everywhere, even one's thoughts, up to the modern regimes, both in the eastern and western hemispheres, that have invented new and upgraded old methods, surveillance remains the basic tool for educating and disciplining populations for an anonymous power. The technological revolution offered even more tools and possibilities, setting a new paradigm in the science of control. These technologies create a net that constantly gets denser, leaving no ground unexploited. More and more, we realise that people’s intimate personal data, what we call private spheres, have been violated in all sorts of ways. Our moments are recorded and turned into “data” in cyberspace. Perhaps we are not far from a dystopian future in which security cameras will scan our biometric data points and, by searching databases, will allow us (or not allow us) access to a city controlled by a modern, sophisticated Panoptikon. I photographed, from the computer screen, moments from the daily lives of people from all over the world, transmitted through thousands of cameras connected to the internet and freely accessible for anyone.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

Local time 13:19:21 2018-05-30

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Local time 18:55:54 2019-02-19

|

|

|

| |

|

Local time 23:46:15 2017-12-23

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Local time 19:47:02 2018-01-04

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Local time 8:41:51 2018-03-31

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Local time 14:55:23 2019-04-03

|

|

| |

Christos Michalopoulos began working in photography in 2009, during a digital photography seminar. Later he attended workshops and courses at university and began being represented in exhibitions. His work deals with social problems in Greece and with questions of surveillance and self-exposure.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reflecting

SURVEILLANCE

An observation on observation

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Observation picture taken by the East German secret police, the Stasi, on September 1, 1983. The Stasi put a numbered dot on the photo, apparently to identify those pictured from a list. Marked with the number 1 is photographer Harald Hauswald. Photo: BstU

|

|

| |

The observed observer

Harald Hauswald, co-founder of the famous Berlin based photography collective Ostkreuz, was the most heavily monitored photographer in East Germany. Hauswald's Stasi file was 1,300 pages long and packed with thousands of details of his daily life. His code name was "Cyclist".

“They called me ‘Radfahrer’ because they thought I had organised a cycling demo, but actually that wasn’t me—I had just helped hire some bikes for a few friends. Naturally I was afraid of going to prison, and by 1985 the state had made it clear they wanted to put me in there for political reasons,” Hauswald said in an interview.

An examples from his monitoring by informants:

“….14.25 o'clock the object "Cyclist" appeared, carrying two cameras, one of them with a telephoto lens. In the gateway he photographed children playing there. From the edge of the opposite parking lot, entrance Kastanienallee 11, "Cyclist" photographed a male person sitting on a park bench at the corner of the pub "Bierstuben….."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

Security notice:

By opening this newsletter, you have given us the opportunity to learn whether you have opened the newsletter, when you opened the newsletter, how many times you have opened the newsletter, and which links you have clicked on and when.

EUROPEAN IMAGES team

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Reading

SURVEILLANCE

A short essay on visual imprints,

meaning and the lack thereof

|

| |

|

| |

How your oversharing helps us

|

|

|

|

| |

We all leave traces of ourselves online. We may think about it less often but we leave visual imprints, too. You may not be anything resembling a high-profile personality but, with a few creative searches, you can find photos and possibly videos online that can reveal a lot more about you than you might think.

There’s something flattening — frankly, something anarchic and altogether liberating — in this proliferation of visual imprints. It doesn’t matter whether you’re sitting, like I am as I write this, at Bellingcat’s office in the Netherlands or lazing on your couch half-watching a bad movie with your phone in your hand. We all, with few exceptions, have access to the same trove of visual imprints. It could be a photo or video shared publicly on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Telegram, TikTok, wherever; it could be a video report published by a news outlet; it could be a high-resolution photo someone posted on Google Maps with their nice new drone on vacation; it could be a split-second frame from a YouTube video.

Visual imprints, however, are basically nothing in and of themselves. Its meaning comes from understanding the broader multitude of relationships that this particular visual imprint has to other things in the world. Those include other visual imprints and contextual information and knowledge, but arguably above all, broader social and political contexts — the foundations of answering why particular visual imprints matter.

For example, you’re an American far-right extremist in trouble with the law back home and you’re in Europe trying to keep your whereabouts on the down-low. Earlier in the year you were ejected from Serbia (because I wrote about you for Bellingcat) and are making efforts to obscure your location in social media posts, like blurring backgrounds or only photographing in front of blank walls that can’t be easily geolocated.

But, in your apparent haste to promote a new hoodie from your far-right fashion brand, you decide to post several photos of yourself posing in front of a wall of graffiti — including one photo showing a piece of graffiti referring to a district of Belgrade, a photo which you delete several minutes later (but not before that guy from Bellingcat saw it and saved it).

Walking around that district of the Serbian capital — because you didn’t realise he was in the same city at the time — that guy from Bellingcat not only finds the same graffiti but, by a coincidence that still boggles his poor mind, physically sees you on a balcony a few stories above, doing push-ups with your shirt off and identifiable tattoos exposed. Given you’re, as far as we know, not even supposed to be in the country, that one image becomes an image with a lot more meaning.

|

|

| |

“Technology can lead you to water, but it can’t teach you how to drink.”

|

|

| |

Visual imprints gain even more meaning thanks to deep, specialist, almost nerdish knowledge that, even if you don’t personally possess it, you can be assured someone else does and is happy to share it. As part of Bellingcat’s Global Authentication Project, we’re documenting instances of civilian harm due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Let's say one morning we see photos and videos from what appears to be a strike from some sort of munition in Ukraine that has injured and killed civilians. Sure, we can often rightly assume from the start that the munition, whatever it was, was fired by Russian forces. Analyzing the direction of damage and impacts, by someone who has experience doing that sort of analysis, can tell us where it could and couldn’t have been fired from. As well as this, fragments of the munition are visible in the photos and video, and someone with specialist knowledge can identify what kind of munition it was and, in addition, if it’s only or mostly used by one side or whether it’s a particularly accurate weapon or not. Looking closely at maps and public information, as well as local reporting, can tell us whether there was likely any legitimate military target in the area or not. This — the relationships between other visual imprints as well as between other pieces of information — is what gives these photos and videos their meaning. In this hypothetical but all-too-real example, we can conclude that Russian forces have killed civilians and thus committed a likely war crime that needs to be investigated by international accountability mechanisms, of which our collecting and forensic archiving of evidence can play a key part.

Still, it usually takes more than just expert knowledge to help ascribe meaning to the visual imprints we find. It takes technology. Fortunately, almost all of this technology is something we all in theory can access and can use methodically yet creatively to help provide meaning to what we see. For instance, let’s say some far-right extremists have posted a video on social media that shows a fleeting glimpse of a landscape in the background. Using image searching tools like Google Lens, even from a mobile phone, to search for some of the features in the background gives a list of a few dozen places across the web the implacable, impenetrable algorithm says might be a match.

The catch, in this instance: almost every ‘match’ is completely wrong. If you follow the links and check out other photos of these locations, you can see pretty quickly it’s not a match. But one of them is the hit you’re looking for; you check and see that there are other features at the location that match with what is barely visible in the fleeting video glimpse you’re looking at. You’ve found the exact location of the video, and then you can ask yourself questions like “what are these particular far-right extremists doing there?” Technology can lead you to water, but it can’t teach you how to drink.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

THE LOCATIONS OF THIS ISSUE

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

Photographers: Rafał Milach, Jędrzej Nowicki, Wolfram Hahn, Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, Esther Hovers, Kadna Anda, David Zehnder, Piotr Tracz, Christos Michalopoulos

Text authors: Michael Colborne

Editorial team: Laura Naum and Petrică Mogoș (Kajet Journal), Karolina Mazurkiewicz, Magdalena Kicińska (Pismo Magazin), Stefan Günther (n-ost) and Ramin Mazur.

Design: Philipp Blombach

Copy Editing: Ben Knight

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

If you like the publication, please follow us on the european images Instagram account!

This is the sixth edition of european images, a project by n-ost, in partnership with Kajet Journal (RO), AthensLive (GR) and Pismo (PL) supported by Allianz Kulturstiftung and the Foundation for Polish-German Cooperation.

Coordinated by n-ost, documentary photographers will meet weekly on Wednesday 6pm CEST throughout the entire period of the project.

If you are a European photographer and want to join the meeting or provide images for the publication please write a short introduction of your work to europeanimages@n-ost.org.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

initiated and coordinated

by n-ost

|

| |

|

|

|

You've received this email because you are a member or a friend of n-ost, AthensLive, Kajet or Ramin or subscribed to european images

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|